Government agencies tend to have a reputation for being dull, unimaginative, and rule bound. Speaking from experience, I can confirm there is good reason for that reputation.

I have to say though that the National Park Service social media accounts can serve as an exemplar for most commercial and non-profit enterprises. There is a engaging goofiness to their posts where they mix humor with educational content about the parks.

Interestingly, the best content seems to be on LinkedIn. Though since they don’t post the same content on every social media site on the same day, I may have missed some posts on Facebook and X that may have appeared further back than I scrolled.

For example, a post today on LinkedIn about splooting (basically animals splaying their bodies out to keep cool) appeared a couple days ago on Facebook.

Last week there was a post that started “It’s not the heat that gets you, it’s the dinosaurs. 🦖 Well, it may be just the heat.” It went on to talk about the importance of staying hydrated during the summer with references to hallucinating about dinosaurs as well as references to Jurassic Park.

💧Drink water often. Stay hydrated and drink before you feel thirsty. Plan to bring extra water just in case you need to place a cup on your dashboard to watch for concentric ripples portending the arrival of a large creature.

The post ends with a picture of a guy in a dino suit eating a park ranger which they caption

Image: This ranger was clearly not hydrated. Costumed dinosaur and a ranger have an awkward encounter in front of the Dinosaur National Monument sign.

There was a really extensive post on Friday the 13th referencing all sorts of horror film lore while warning about approaching animals and living camp fires burning.

3: Like, he’s not that cute. 🦬

Oh my gosh, like, as if! That squirrel is, like, totally adorbs with its fluffy tail and those cute little paws. And that bison, like, needs a friend for sure, but, like, let’s not forget that squirrels can totally bite, especially from the bitey end, and that the bison has all the friends they need. Now, like, who packed the bandages and the extra leg splint?

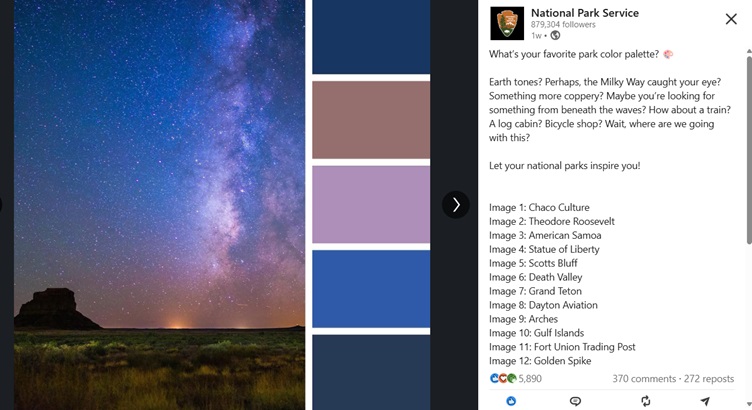

However, one of my favorite posts in recent weeks was one where they asked viewers what their favorite National Park color palette was and matched palettes up with 12 different National Park sites.

We talk about how arts organizations need to emphasize their value to their communities. National Park Service social media staff does a great job of communicating that value and capturing the national imagination.

Santa Cruz Shakespeare has several tiers of benefits for donors/members. Some, like season-announcement parties, are open to several tiers. Some,…