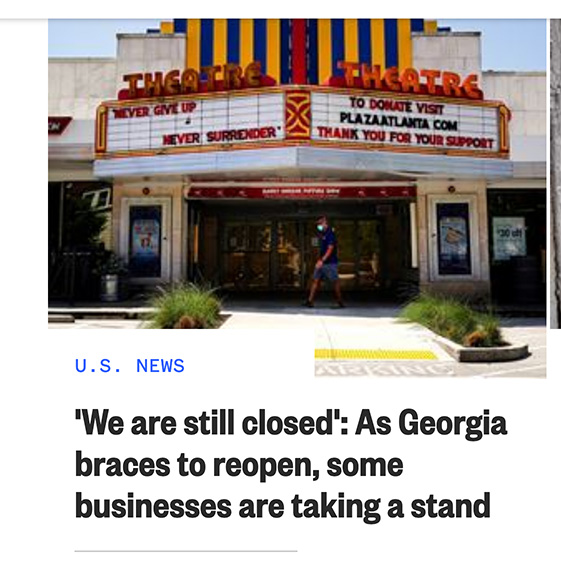

To continue where I left off from yesterday’s post about the UNESCO document, Culture in crisis: Policy guide for a resilient creative sector, the next section addresses providing support for cultural and creative industries in the wake of the Covid epidemic. Whereas the policies covered in yesterday’s post were more targeted toward helping individual artists and organizations, this section is more focused on broader sectors. This part of the document has seven separate sections, but I don’t intend to take screenshots of them all. Some of the proposals aren’t as relevant to non-profit arts organizations so I will summarize rather than going into detail.

The measures proposed in this section include: Accelerated payment of aid and subsidies; Temporary relief from regulatory obligations; compensation for business interruption losses; relief from taxes and social charges; stimulating demand; preferential loans; strengthening infrastructure and facilities.

Since I am writing from the bias of a U.S. based non-profit, some of these measures aren’t as significant as others. Accelerated payment of aid is basically the suggestion to pay disbursements on grants already in place rather than waiting for final reports or the completion of services in order to allow organizations to remain liquid and finish all that stuff.

Relief from regulatory obligations as described in the document are focused on broadcast networks. I am not sure there are a lot of regulations in the U.S. that are inhibiting organizations from staying liquid and aren’t important for protecting workers and participants (i.e. those that deal with employment, health and safety, supervision of children in camps).

Similarly, relief from taxes doesn’t impact a lot of non-profit arts organizations. In some locations where the organization is making a voluntary payment to local government to support infrastructure, some discussion about payment is probably worthwhile. For those organizations that pay local/state sales tax, getting that removed in a time when tax receipts are way down is probably an extremely difficult conversation.

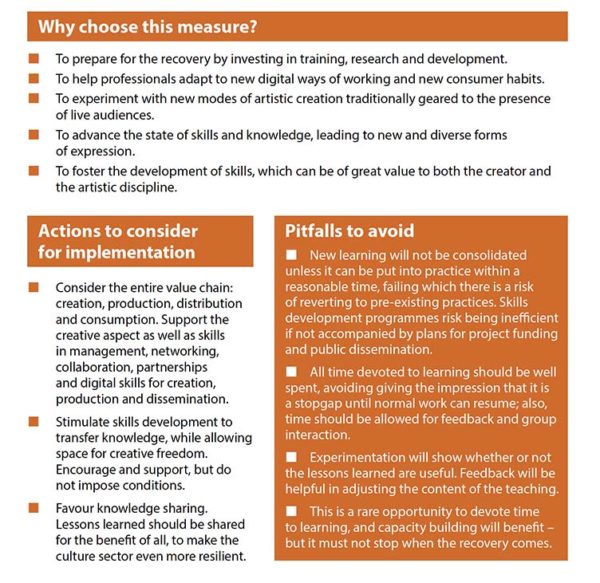

The preferential loans section is a valuable proposal, but the content of that section can be summarized as: The loans should be made, but the banking sector has insufficient understanding of the variations in creative organizations necessary to evaluate them for creditworthiness for loans so the banks need to be trained first.

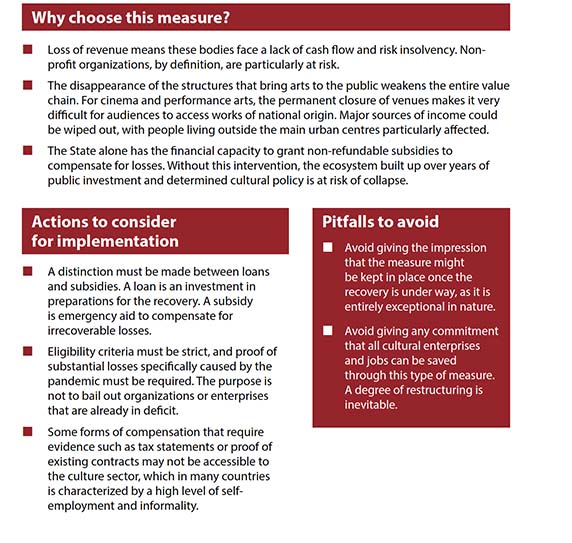

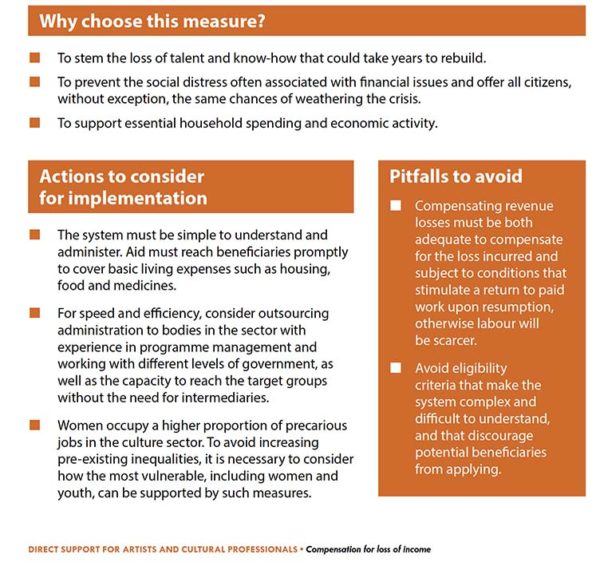

Compensation for business interruption loss of course is a big issue, especially in terms of insurance paying claims. This section definitely is definitely worth reading since it is so relevant and balances the concerns of both government and industry.

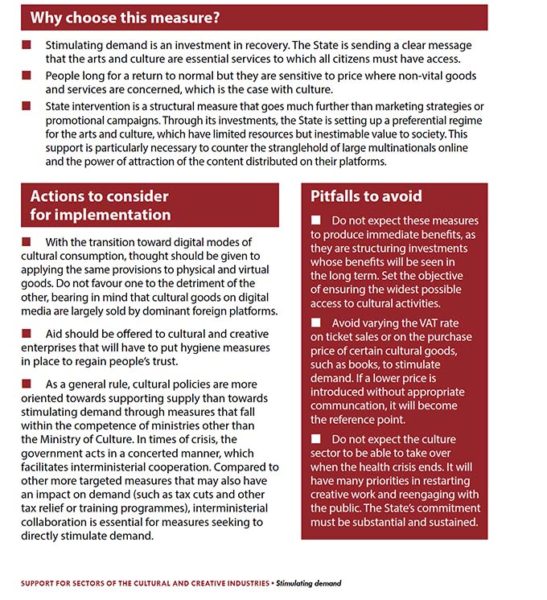

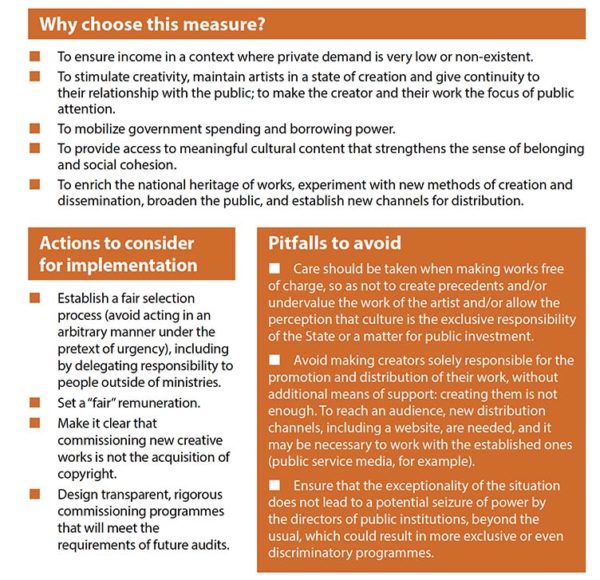

Stimulating demand is a really interesting section and something folks in the U.S would love to see the government embrace. Look at that first line “The State is sending a clear message that the art and culture are essential services to which all citizens must have access.”

I appreciated the fact they noted change and results wouldn’t happen immediately and counseled a long term view.

I also think the observation that ministries of culture (or the NEA in the case of the US) does not have the expertise to stimulate demand is valuable to note. This is something extremely important to acknowledge when it comes to discussions about elevating arts & culture to Cabinet level position in the U.S. government. It isn’t enough to have someone in the position, the overall policy and practice of the government must be aligned toward cultivating both supply and demand. Even if the culture secretary/minister portfolio doesn’t have the ability to stimulate demand, government policy should be that those that do work hand-in-hand with the culture secretary/minister toward that end.

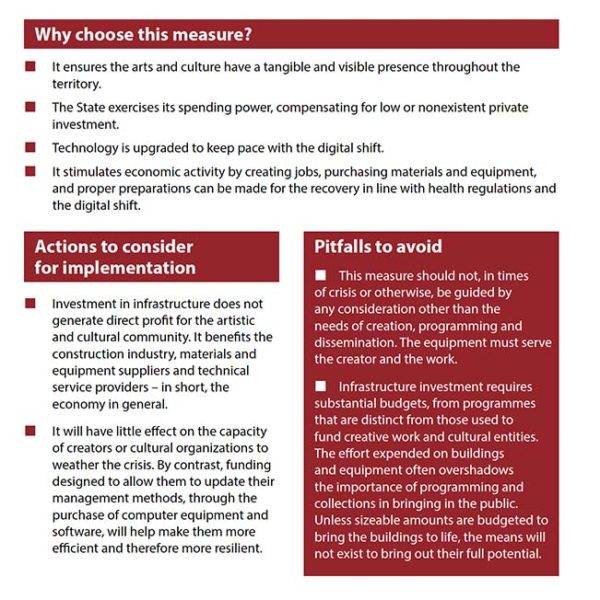

I debated whether to take a screenshot of the Infrastructure section because it states the well-known and easily summarized “Edifice Complex” truism. People like to fund impressive looking structures, but don’t want to fund the programs or people or programs that will inhabit the structures. However, I feel like we can all use the vindication:

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…