I have been cautioning the non-profit arts community about citing the economic value of the arts for over a decade now. The first time was in 2007. I wrote about it a few times in the interim, but I didn’t really start to devote time and space to the idea until the last 2-3 years.

However, if you don’t put stock in my arguments, perhaps you will find statements by celebrities with English accents to be compelling. Check out the following videos from an Arts Emergency Service convening at the Oxford Literary Festival where author Philip Pullman (His Dark Materials series) makes the same point cited in just about every piece I discussed in previous posts:

“Keep clear of economic justifications for the arts. If you do that, if you try that, you hand a weapon to the other side because they can always find ways of proving that you are wrong about it, you’ve got the figures wrong. You invite them to measure everything in terms of economic gain. My advice would be to ignore economic arguments altogether.”

Noted graphic novelist Alan Moore chimed in about “…the ridiculousness of, sort of, having to have impact. To appoint words like that to the arts, its criminal, its ridiculous.”

Pullman makes another statement that aligns with the assertions by Carter Gillies I often cite that just because something can be measured, doesn’t mean the measurement is relevant. (Diane Ragsdale also wrote a piece along these lines.)

“The government, you see, asks us to do something and then gives us the wrong tools to do it. [unintelligible] says, ‘Look I want you to measure this piece of wood. And here’s a tool for you.’ And gives you a grindstone. And one thing you can say is, ‘Why do you want to measure this wood anyway? This is firewood, I’ll burn it to keep myself warm.’ Questions arise from that. What is the right tool for measuring the arts and do we need to measure them anyway? What are we measuring them for?”

There is another video on the Arts Emergency page where the panel, which includes Arts Emergency co-founder, Josie Long, discuss the false dichotomy between art and science that is worth checking out.

As I was looking back at all the posts I made on this subject, I found the following tweet I had linked to many years ago. It struck me that if you can’t entirely control the language your advocates use, request they make this one small change in terminology can help start to shift the “economic benefit” mindset. (Though perhaps not something to use in the context of immigration discussions.)

Instead of using the phrase "I'm a taxpayer" to legitimize a comment about government, we should use the universal phrase "I'm a citizen"

— Dan Johnson (@DanLikesVoting) March 28, 2012

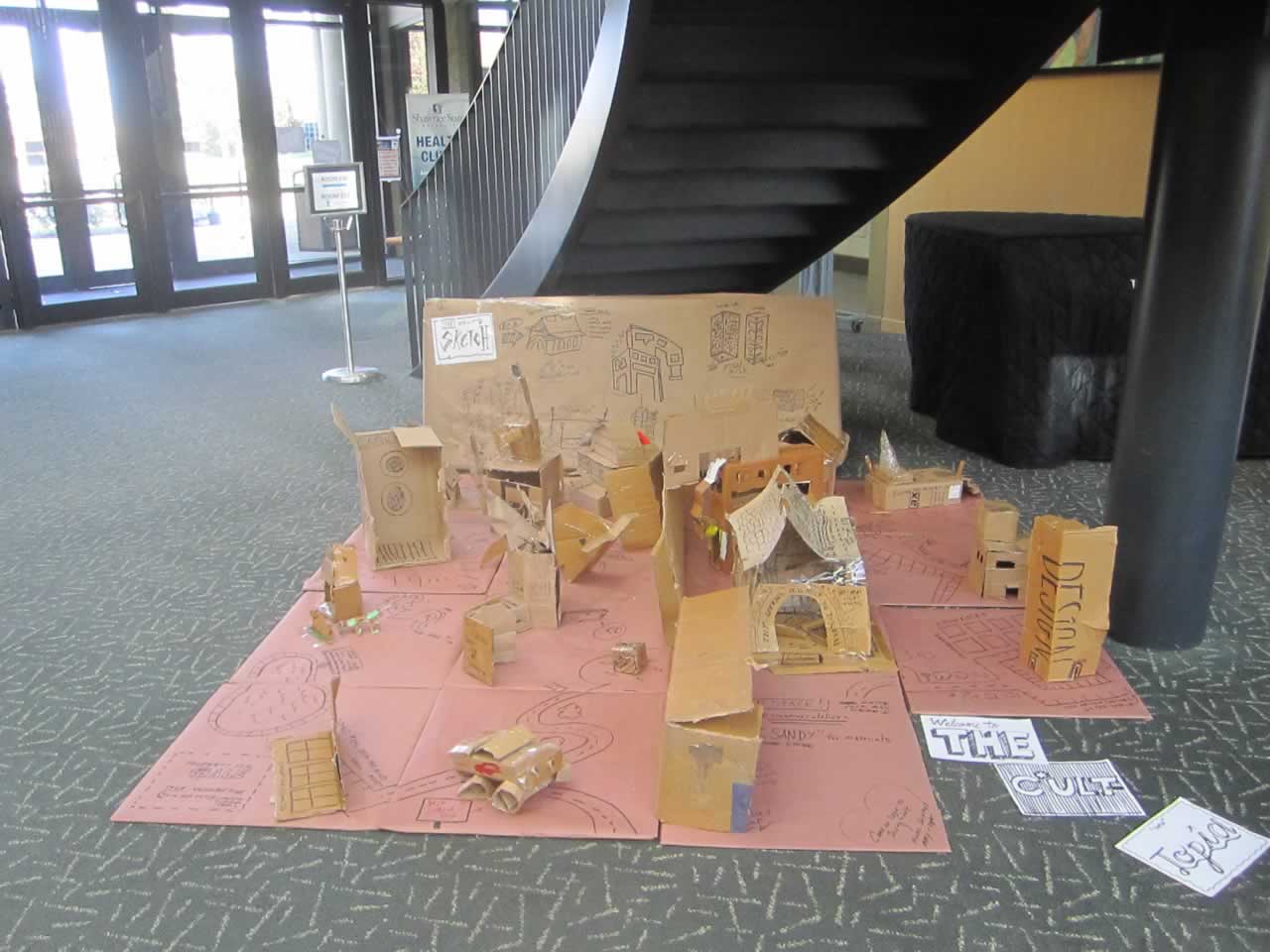

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…