As a follow up to yesterday’s post on the Creative Placemaking conference I attended, I wanted to share some general thoughts and ideas I had picked up.

Regardless of whether the setting is urban, suburban or rural, there are a number of communities experiencing really difficult times. A number of panelists discussed the need to address the community trauma before you ever talk about economic stimulus. You can’t just walk in and position something as a solution to the problems in the community until those problems are aired and people have a sense that they can move forward from there. Otherwise the issues will likely continue to fester and undermine the foundation of what you are trying to accomplish.

When it comes to investment and grant making in rural communities, it probably won’t come as a surprise to anyone that one of the factors contributing to the low level of investment is geographic remoteness. David Stocks of the Educational Foundation of America (which ironically is not involved in education) talked about how program officers will need to invest a lot more effort into bringing support to rural communities.

They might need to take a plane to a regional airport and then drive 2-3 hours before they reach a community. There is also the issue of trying to identify what organizations would make good anchor partners for the work they do. There is a need for both funders and community organizations to work at expanding their relationship networks to increase the chances that their orbits will intersect.

Marie Mascherin who works for New Jersey Community Capital, characterized her organization primarily as a lender. She talked about how lenders viewed placemaking activities which was a perspective you rarely get. All the same, she warned those in attendance that her organization was atypical in that they got a lot more involved with the community and projects they were working on than most similar lending organizations.

John Davis who was involved with bringing vitality to both New York Mills, MN and Lanesboro, MN passed on a piece of advice he had received from a college professor – don’t make excuses, even about money, for not finding a creative solution. Basically, don’t let lack of money (or other things) become default excuses about why things can’t be accomplished. In a rural setting where resources are scarce, you pretty much have to try harder to find creative solutions.

(Honestly, “work even harder and don’t make excuses,” wasn’t something I wanted to hear, but wasn’t exactly news.)

Davis also talked about an argument he made to a local government that was balking at renovating a building. He noted it would cost them $35,000 to demolish the building or they could invest $35,000 into renovating the building and have a more valuable property they could sell later if his project failed.

His project didn’t fail, but that concept dovetailed in an interesting way with a comment Ben Fink of Appalshop made about a prison project being proposed near Whitesburg, KY. He said that the $300,000,000 prison was being sold to the community as, at best, creating 300 new jobs. He noted that was $1,000,000 a job–compare that to how much benefit $1 investment in arts and culture has for a community.

It occurred to me that is something to look into and leverage proactively with governments and decision makers. Rather than waiting until it comes time to ask for funding to be renewed, when a discussion comes up about providing tax breaks or subsidies for companies, it might be useful to mention that $1 invested in creative placemaking/arts/culture/education in the community is more efficient.

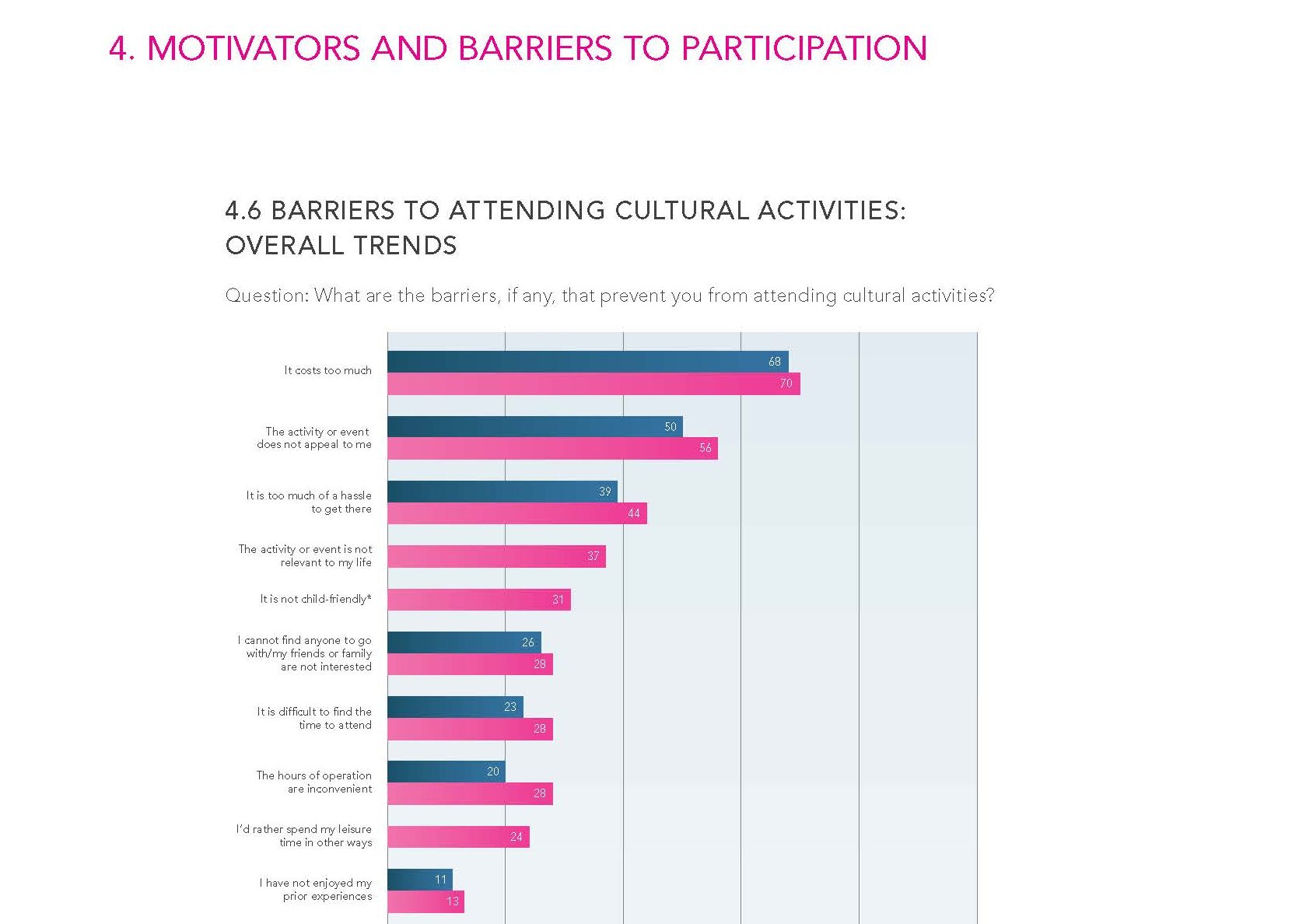

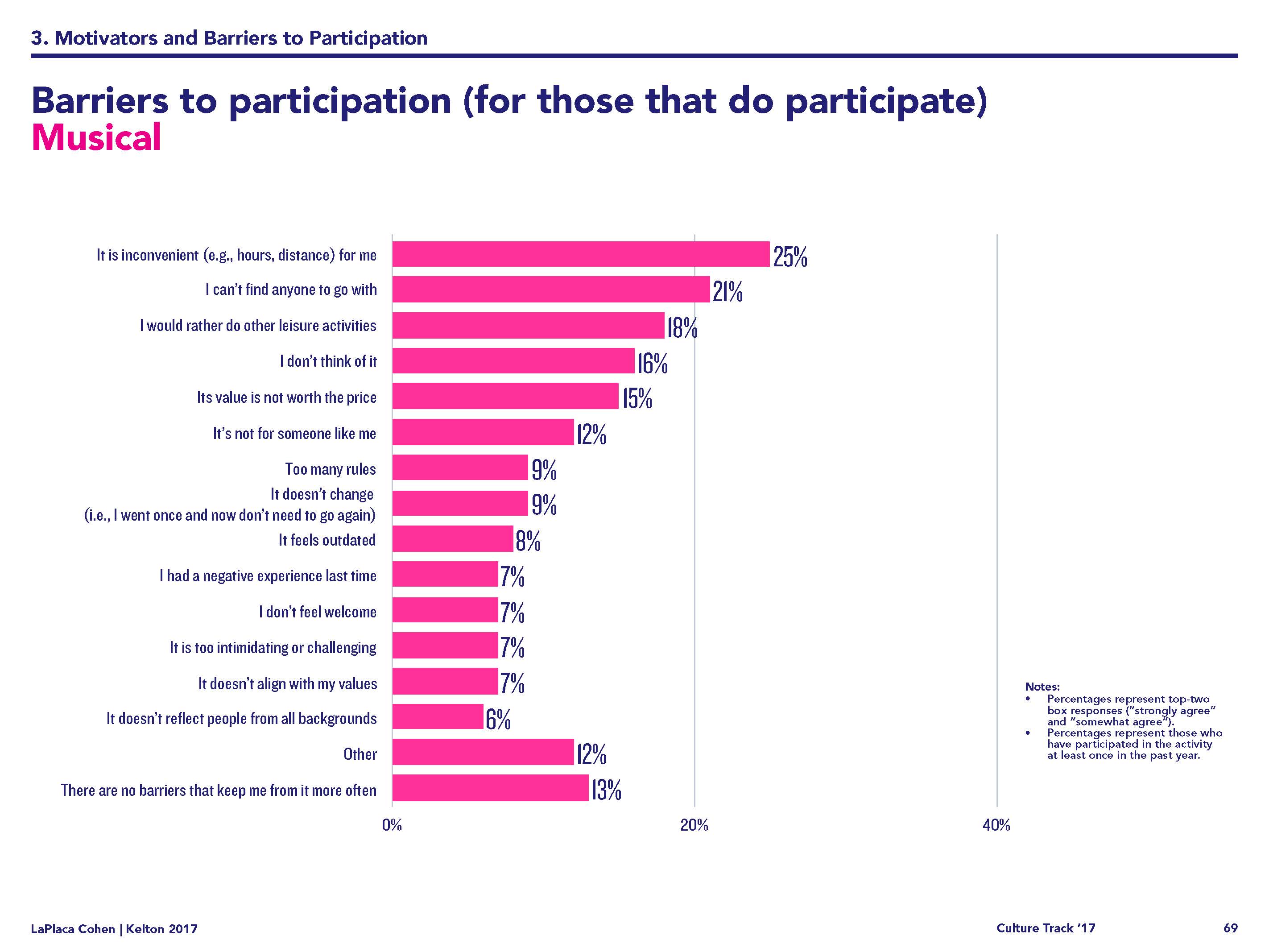

While I am on the subject of economic activity, in one session I bluntly asked Jeremy Liu of PolicyLink about the veracity of economic impact claims being made by organizations and communities. He said if they are using analytic tools like those offered by Implan, the numbers are dependable.

In the past I have mentioned my concern with arts and culture organizations arguing for funding or policy changes citing the benefits of art and music on learning and test scores when such benefits are only weakly supported or have been debunked.

What has worried me is that decision and policy makers will learn about the lack of evidence for these claims and perhaps actively wield it against the arts community. By the same token, I have often wondered at the rigor behind claims of economic impact of creative activity in communities and feared what might result if they are debunked.¥

A few other tidbits people offered-

Don’t become hyperfocused on placemaking. Don’t value place or a project over the community. Even if you are in a group, no project is completed in isolation.

If you recall in the very beginning of my post yesterday I mentioned that I gained an appreciation and broader perspective on the different roles that contributed to a placemaking project from governments to funding/loan group to community members to the people executing the work, placemaking is a function of many entities working together.

I feel like I am citing him a lot in these last two posts, but I appreciated Ben Fink’s insights about establishing relationships with people in the community. He said the first real shared connection you will make with someone is rarely associated with the project you are trying to accomplish. As an example, your aim may be to solicit participation in a building renovation for a maker space but the initial basis of your relationship is a shared interest in 19th century steam engines.

He said that building community support and participation happened in the same way friendships develop. It is heavily dependent on the dynamics at the formation of the project. If participation is by invitation only, one person ends up being in charge. If you form a clique of interested parties, it becomes insular. But if the project begins with the intention of leaving the door open, interested people will start to gravitate toward the project as they see work happening.

¥- None of this compromises my assertion that while arts and cultural activity may generate economic activity, steady employment, positive social outcomes and quality of life, the none of this is a measure of the value of arts and culture.

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…