When discussion turns to how audiences were once pretty raucous but are now expected to sit quietly, you get the impression that those times are long past. Those who are plugged into the opera world are probably aware, however, that at least a certain segment of the audience at La Scala is still pretty vocal. According to a piece on History Today, in 2013 the opening performance of La Traviata was accompanied by catcalls and hissing.

…having interrupted the performance several times with noisy catcalls, they rounded off the evening by booing loudly during the curtain call. The cast were devastated. The Polish tenor, Piotr Beczala – who had sung the part of Alfredo Germont – was so appalled that he refused to perform at Milan’s most celebrated cultural landmark ever again.

It wasn’t the first time that the loggionisti had made their feelings heard. In 2006, the Franco-Sicilian tenor Roberto Alagna stormed off stage midway through a performance of Verdi’s Aida in protest at the furious cries that were hurled at him. Even the great Luciano Pavarotti was not spared the loggionisti’s wrath. In 1992, he was booed while playing the title role in Verdi’s Don Carlo.

Shortly before taking the Artistic Director post in 2014, Alexander Pereira, declared his determination to stamp the practice out.

The loggionisti, however, disagreed. Believing that the audience have every right to take sub-standard singers to task, they have continued to raise merry hell.

While we may want to cite numerous interruptions by cellphones, talking, consuming food, etc that occurs these days as a similar manifestation, note that the loggionisti are, at least theoretically, invested in paying attention to the performance and are relatively knowledgeable.

Though when you are talking about interruptions, that is perhaps a distinction without a difference. I wrote about similar situations before when audiences in the US were so invested in performances, they might complain during a show when an actor’s interpretation of Shakespeare didn’t align with their own.

Reading the History Today piece, you might start to think history repeats itself with its discussion of designing pieces to suit short attention spans.

Realising that no audience would listen to an entire work, composers started to produce pieces that took account of their inattention. These often included an aria di sorbetto (‘sherbet aria’), an incidental passage that allowed the audience to buy food or drink without fear of missing anything important.

Like most articles on this topic, it credits Richard Wagner’s influence and demanding plot structure as the reason audiences started to sit silently and pay attention. The fact Wagner’s name inevitable comes up as the reason for this change makes me wonder at the veracity of this claim. Could he really have been that influential or is everyone who writes about this reading from the same source (or quoting sources that all quote that original source)?

The History Today article does say that societal changes were of greater importance in the effort to bring peace to opera houses. It suggests that with the wider variety of entertainment options available in the informal atmosphere of music halls, opera houses got quieter, leaving those that appreciated opera a growing appreciation of the silence.

What implications might this have for the current cultural environment? There are pretty strong indications that people appreciate the convenience, informality and variety of entertainment available to them at home via streaming services/video games/general Internet.

I might have come to the conclusion that cultural organizations should therefore offer a wider variety of programming in an informal environment. However, the Seattle Symphony findings I wrote about on Monday make me reconsider that. Their newer audiences gravitated toward the informal, short programming certainly, but it was also the most narrowly programmed season.

Granted, they are a single organization practicing a single cultural discipline which ultimately constitutes a pretty minuscule sample. But reading about it makes me pause before making any blanket statements. The only thing that is easy to say is this is a complex situation requiring careful thought.

There has been this assumption that newer works that connect with the tastes and values of younger audiences need to be presented rather than returning perennially to the old warhorses. But as I wrote in an email to Drew McManus, it turns out, for the Seattle Symphony at least, that the audience open to the most eclectic mix of programming is the one that is dying out.

As I say, this may only be true for a single organization and/or classical music. It made me a little embarrassed to think that an apology might be owed to a devoted audience that has been characterized as stodgy and tradition bound when it turns out they might be the radicals.

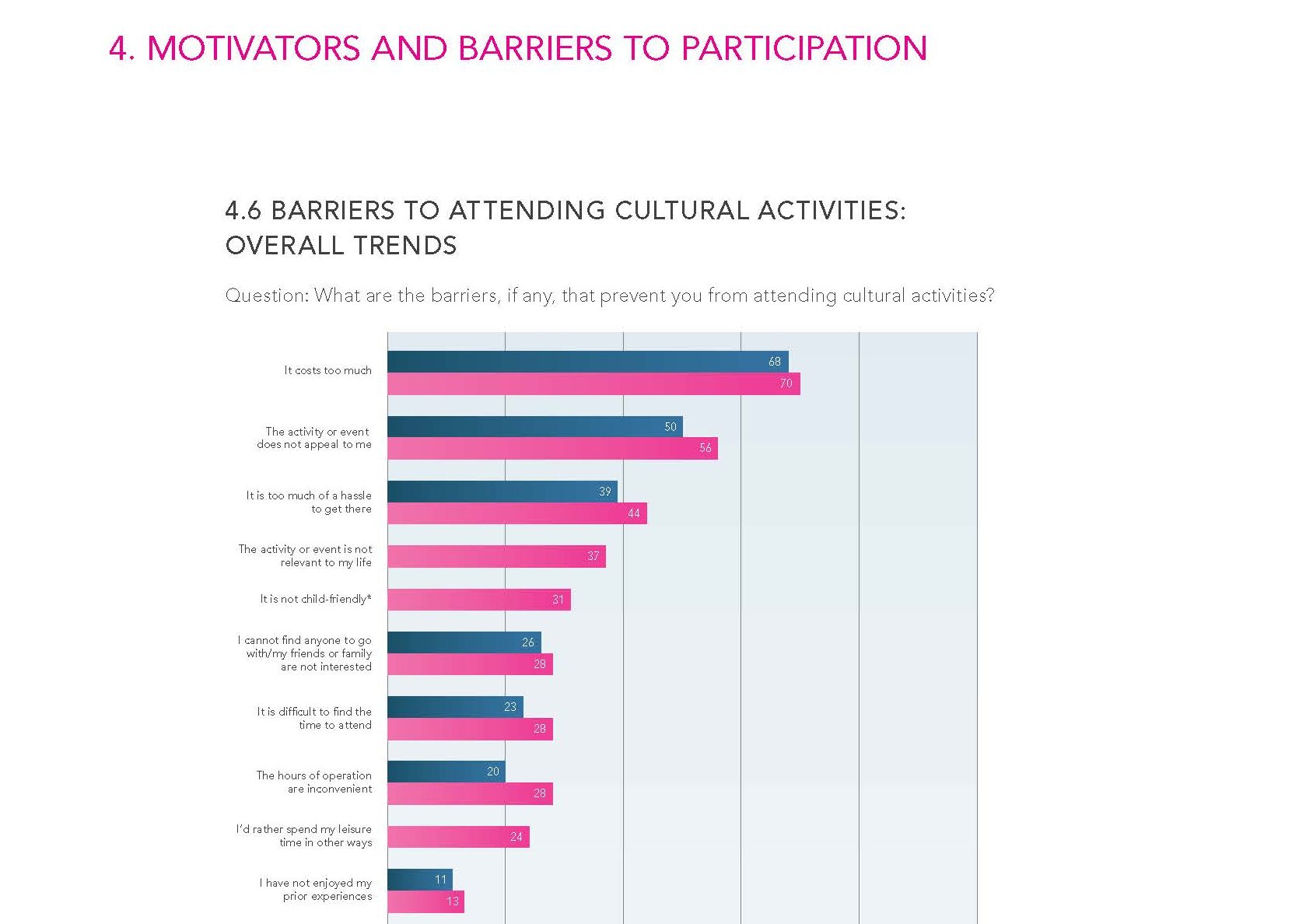

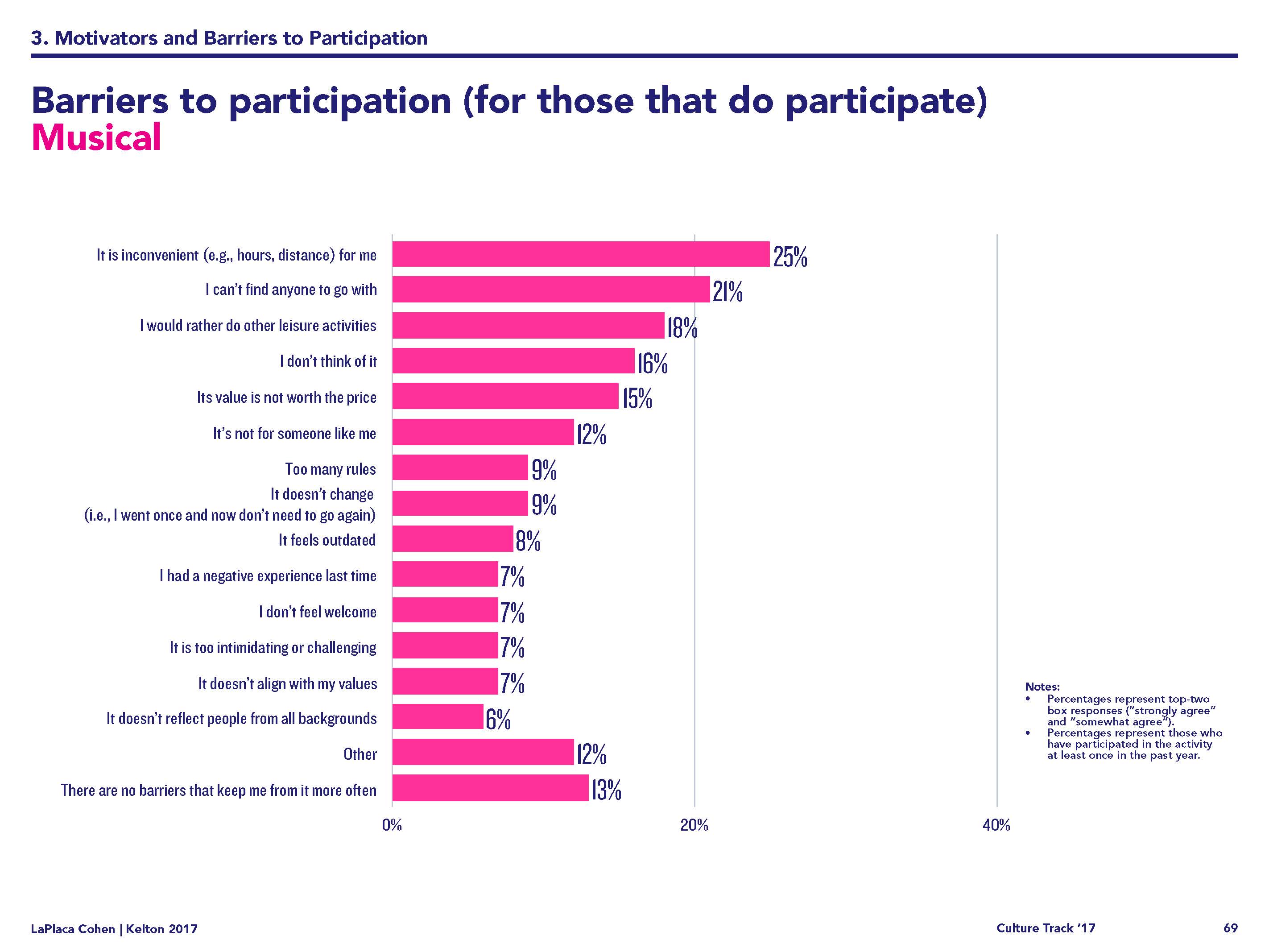

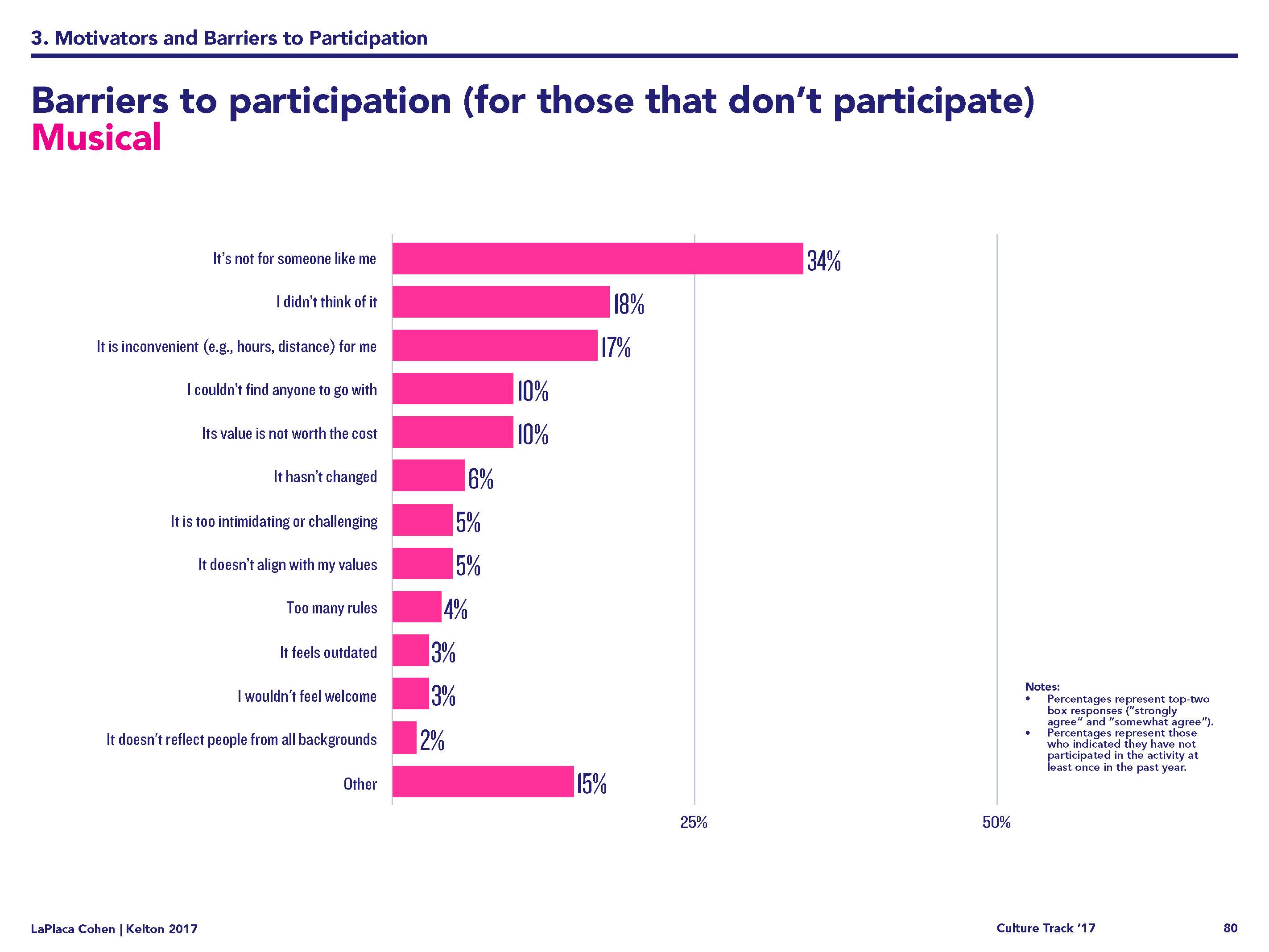

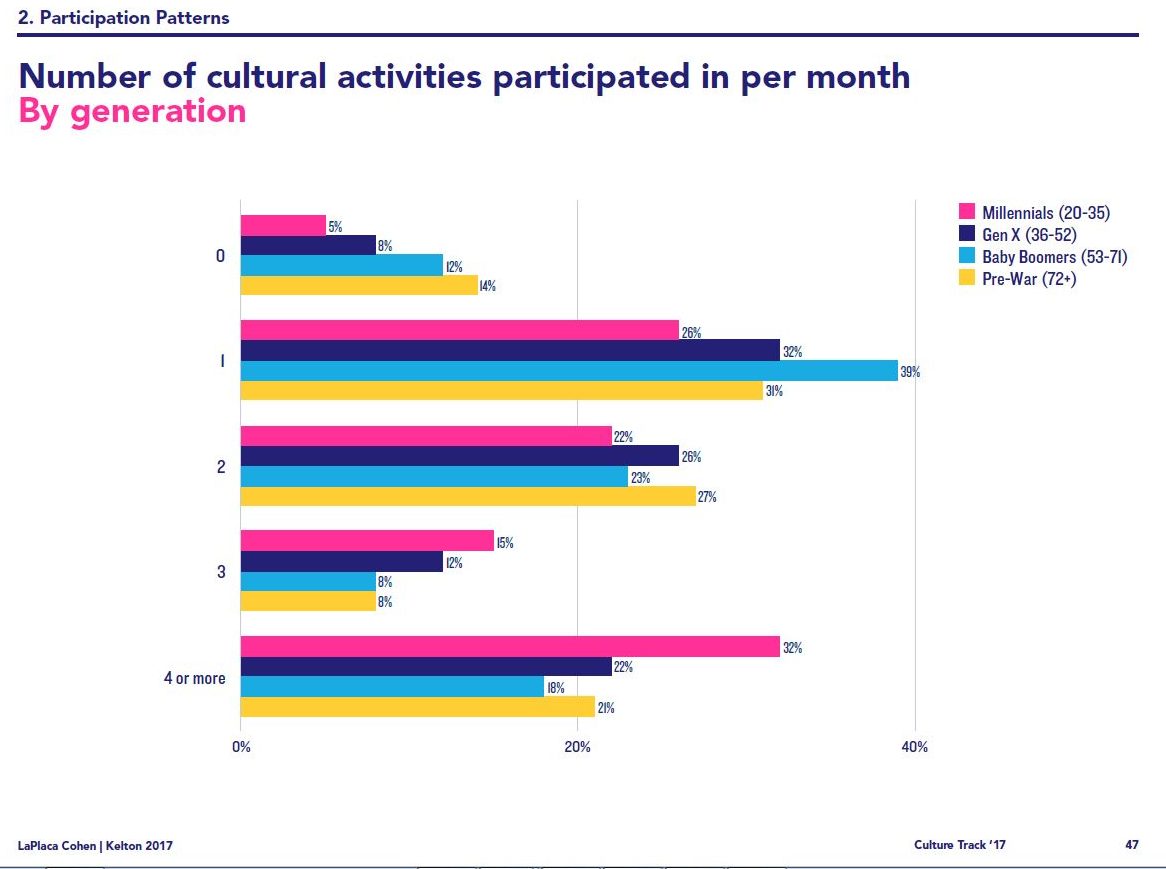

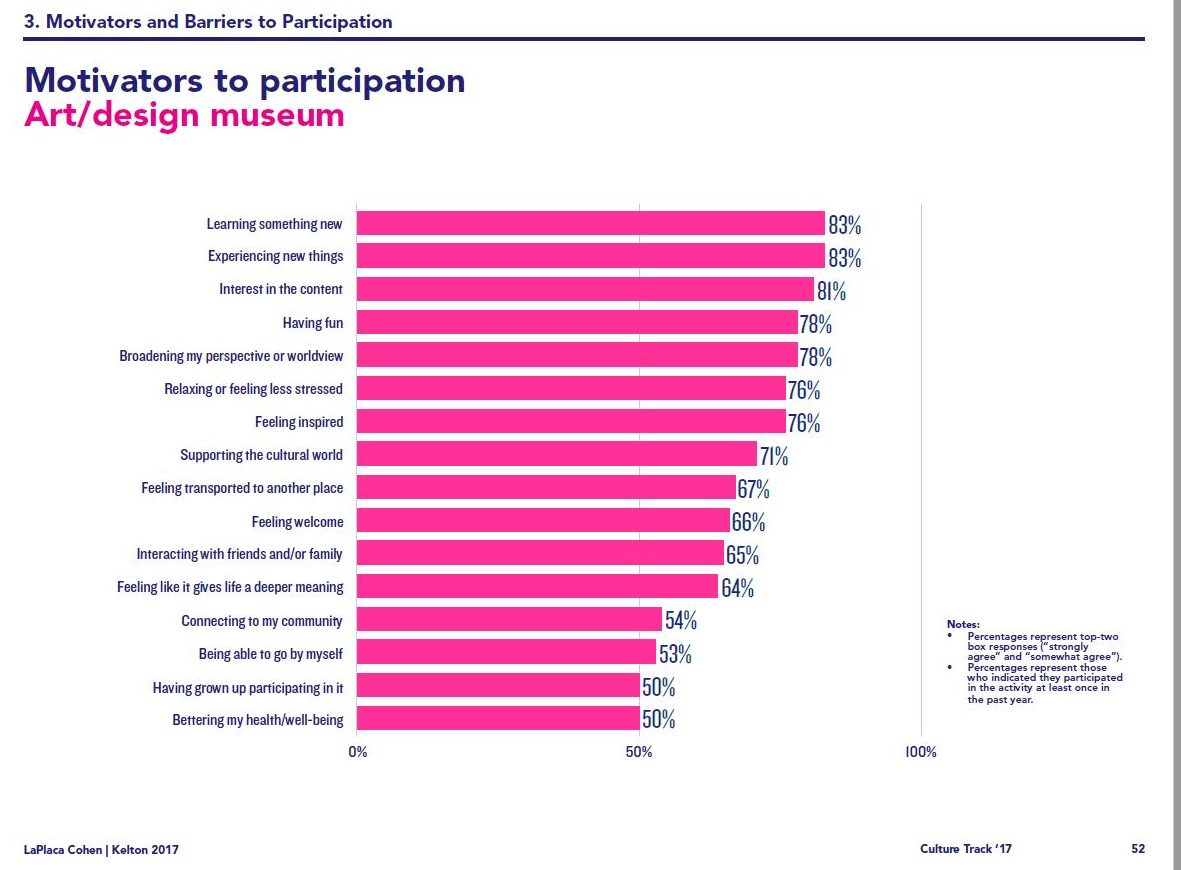

Getting back to the History Today article. As much as I don’t want a return to the chaotic environment described in articles like this, I continue to return to the subject to remind myself (and you) that we need to keep thinking about the environment we are providing. When I wrote about the Culture Track study last month, I used a lot of slides related to motivators to visit museums and galleries but the slides for live performance events are similar.

The top motivator across most genres was Having Fun, second was Interest in Content, followed by things like feeling inspired, new experiences and social opportunities with friends. People aren’t looking to scream across the room at their friends and wreck the place. There is a strong interest in the content and its value as well.

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…