Hat tip to Jari-Pekka Raitamaa who tweeted an article about mistakes people make when considering founding a tech start up. It occurred to me that the same basic advice could be given to people thinking about founding an arts company of some sort.

The basic premise of article by Jolie O’Dell, Stop founding! 10 signs you’re ‘employee material’ is that many would be founders need to get some significant experience working in a company before they decide to start one. And even then, they may be better suited staying as an employee.

You’ve never tried a real job

[…]

If all you’ve tried so far is freelancing, consulting, or agency work, founding is a pretty big leap. You don’t know about how companies run from the inside, about different management styles. You might have trouble forming and functioning in teams.

Why this is bad for founders: Founding requires commitment and longevity. Regardless of your C-suite title, in day-to-day operations, you’re functioning as a team lead responsible for managing a small crew of professionals. Experience in management with a corporate safety net is a boon.

Along the same lines, if you have only worked as a performer or only done short term administrative work for an arts organization, you may not have the skills and endurance to lead a small group through the rough formative years of the company.

You’ve already failed at one or more startups

We fetishize failure in the startup community, and we especially fetishize failing quickly. But regardless of the lessons you learn or the network you build, failure is still a bad thing.

In and of itself, failure is the universe telling you that your idea wasn’t good enough.

And it’s got nothing to do with execution. It’s your idea. Twitter was really poorly executed at first. It succeeded. Ditto for Facebook and lots of other consumer software. Ditto for a lot of programming languages. You can have wiggle room in execution for a truly great idea.

Why this is bad for founders: A string of bad ideas is more than just “throwing [stuff] at a wall and seeing what sticks.” It might be a sign that you’re jumping in too deep, too quickly. Fail at a few side projects, if you must. But be cautious about rushing into a new venture with nothing but failure under your belt.

The bit about fetishizing failure and failing quickly and often caught my eye (so my emphasis) because non-profit arts organizations are often criticized for their conservative approach and unwillingness to take chances and flirt with failure. To some extent, it may be to your credit to have embarked on a new endeavor and failed.

Still it is easy to fail as a result of ill-informed and conceived choices. The article makes good points about making sure you have learned from your mistakes before proceeding.

You can’t design or code (Translate as “You Can’t Directly Contribute To The Product”)

Lean startup culture says you need three archetypes for a startup: a developer, a designer, and a hustler. Traditionally, the hustler does biz dev, sales, hiring, and management tasks.

But what does a hustler do at a founding-stage startup, really? It often turns into long hours for long hours’ sake, lots of meetings with few outcomes, and boatloads of cheerleading and enthusiasm for a business that’s generating no income and has few or no users.

If you can’t pinpoint your exact skill set — and if your skill set isn’t unique, valuable, and directly related to product creation — you might want to take an employee position at a later stage company.

Why this is bad for founders: Creating a minimum viable product is often Task Number One at a lean startup. Your salary shortens the runway for such a nascent company, and you can’t sell, aka “hustle,” against a product that doesn’t exist yet.

While it might have been good to trim this one down, the bit about the hustler putting in long hours for long hours sake and doing a lot of cheerleading struck a chord.

True, the crucial function in an arts organization ends up being fundraising. But I am pretty sure the time is coming soon if it hasn’t arrive yet, given the expectations created by Kickstarter and its ilk, where it will be difficult to raise any sort of funding without some sort of interesting product example.

I suspect people won’t be as willing to give based only on the idea of a promising group creating good art. Unless you are in a position to pitch in and produce from the get go, your presence may be a hindrance rather than a help.

Paul Allen and Bill Gates didn’t bring Steve Ballmer on to run the business side of Microsoft until five years after the company had been founded and provided its first piece of software.

The arts are already full of people working unnecessarily long hours, don’t add yourself to their number.

Which leads to the next point:

Your big idea is unoriginal

[…]

If the market is saturated with variations on your idea, back slowly away from your drawing board and wait for your next big idea.

Why this is bad for founders: With too many competitors come too many problems. You might not be able to wedge your way into a crowded marketplace. Or you might get suddenly squashed by a drawn-out patent or other IP lawsuit.

Along the same theory that people probably won’t give to groups without a demonstrable product, new funding for old ideas and methods of producing art is probably not long for this world either.

Again, along those lines…

You don’t know what you want

Why do you want to be a founder? This is brutally difficult territory and requires immense passion and Herculean dedication.

Scratch that: It requires Odyssean dedication. You’re on a quest with no end in sight. Every task seems impossible. There are new difficulties around every corner.

So why the heck would you want to do that?

If you don’t have a clear vision, if you’re only running on the heady fumes of startup mania, you will most certainly fail.

Why this is bad for founders: Enthusiasm only goes so far. Only a heart and mind obsessed with a specific mission will be able to sustain you through the hard times that await you.

Again, founding an organization out of simple rejection of the current choices isn’t enough. Your vision can’t be predicated on, “We will different from them and do it better.”

What does that look like in practical terms? It isn’t enough to say you will be nimble and more responsive to change, you have to have an idea of what practices and infrastructure you need to have in place to make it happen.

The other signs Jolie O’Dell lists that I haven’t expounded upon are pretty apparent or closely related to the points I have already made: “You’re young and/or inexperienced”; “You have no network”; “You get bored really quickly”; “You have no net worth”; “You’re the primary breadwinner of a multiperson household.”

I am not saying people shouldn’t found new organizations. It seems pretty clear we need new ideas and new methods. These are just some important things to consider before you undertake such an endeavor.

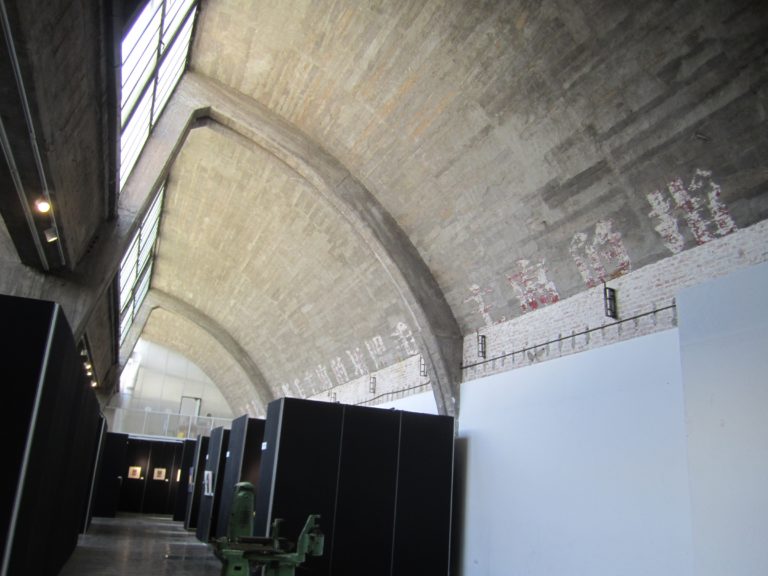

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…