Last week Drew McManus did a call out to the non-profit arts community to submit proposals for the Nonprofit Technology Conference in March 2019. (Proposal deadline is August 17)

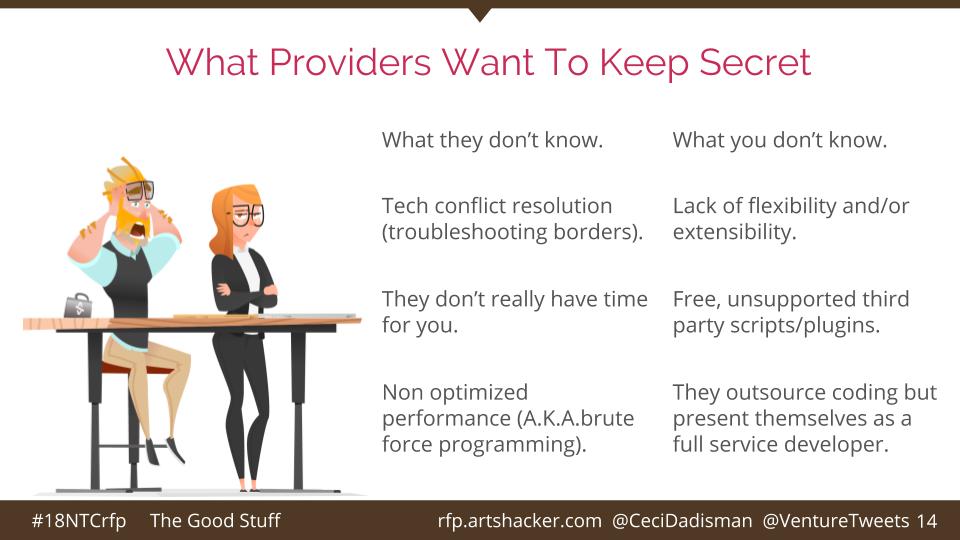

Last year, I was excited by the topic Drew was presenting – “Everything Tech Providers Wished You Knew About Writing A RFP (plus the stuff they want to keep secret)

So in the spirit of getting more stuff I am interested in learning about proposed, I am gonna give you a list of some of the things I think would make good topics in the hope some of you will submit something.

- Data Privacy and Security From Perspective of Communities of Color – I have already reached out to one of the people who made a presentation for the Hispanic National Bar Assn in NYC, but anyone with an interest should submit on this topic. Given that non-profits serving communities of color often need to establish a relationship of trust, this seems like an important subject to address.

- Analyzing The True Cost of Programs – favorite topic of mine. Related idea:

- Using Evidence/Data to Rebutt the Concept of Overhead Ratio As A Measure Of Effectiveness

- Shared /Online Procurement Goods/Services

- Effective RFP Generation – both internal & external processes

- Using Geofencing To Better Understand Target Communities – can geofencing help you better understand a community based on where they travel around the community?

- Ethics of Using Geofencing For Marketing – i.e. I can geofence a local theater and target people based on the idea that they enjoy attending performances or with the intent of stealing the audience.

- In-Person/Conference Based Professional Development vs. Online/Technology Delivery. Are there some subject areas better suited to one format over the other?

- Shared services/technology arrangements – in terms of both back office and program delivery

- Delete the Facebook Account? – Communication strategies when faced with a concerted social media assault

- Conforming with Google’s new criteria for Adwords Grants – i.e. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2018/05/07/nonprofits-can-keep-adwords-grants-following-major-changes-restore-lost-accounts/

- Energy Saving Performance Contracts

- Use of technology to provide regular cues to keep strategic plan alive and relevant – i.e. using software/apps to periodically to nag/remind you of milestones in time line, provide encouragement, remind you of ideas you had during the planning session

- Effective Hiring – from job description to orientation/training this topic is large enough to be multiple sessions can hit on everything from online job boards/job app apps to new state laws requiring salary range and forbidding asking about salary history

There are plenty more ideas where these came from, but I feel like this is a good broad range of subjects. I have already reached out to a few people encouraging to propose based on topics they are well-qualified to address.

If any of this inspires you in any sort of direction, submit a proposal. If you got questions, let me know. Like Drew, I am on the conference session committee. Honestly, the conference organizers are really good about providing opportunities for people to ask questions at scheduled office hours and open Q&A sessions, and an online proposal prep group in which you can solicit feedback on proposals you are developing. All these resources are listed on the proposal pages.

Santa Cruz Shakespeare has several tiers of benefits for donors/members. Some, like season-announcement parties, are open to several tiers. Some,…