In my post yesterday, I quoted Matt Burriesci as he addressed how uncomfortable people feel when it comes to advocating the intangible value of the arts.

We should stop being ashamed to believe in a value that cannot be weighed, measured, cut, or quantified — and to try and convince others to believe it, too.

I’ve floated these ideas to a few of my friends who work in the arts — privately, of course, because one never wants to utter such things in public. Almost all of them have said the same thing, and in the same weary, confused voice: “Well, yeah, Burriesci, I mean, I agree — but that’s just idealism.”

This line of thought pretty much illustrates how uncertain the arts community feels when it comes to trying to justify the value of what they do. How do you validate results that are difficult to measure?

Fortuitously, Seth Godin helps to provide an answer in a context we can all understand — the value of soft skills in the workplace.

Now obviously, these same soft skills are valuable outside of the workplace, but so much of what we value as a society is in the context of economic benefits.

Organizations spend a ton of time measuring the vocational skills, because they can. Because there’s a hundred years of history. And mostly, because it’s safe. It’s not personal, it’s business.

We know how to measure typing speed. We have a lot more trouble measuring passion or commitment.

Organizations give feedback on vocational skill output daily, and save the other stuff for the annual review if they measure it at all.

And organizations hire and fire based on vocational skill output all the time, but practically need an act of the Board to get rid of a negative thinker, a bully or a sloth (if he’s good at something measurable).

He likens someone whose poor skills detract from the productivity of the workplace with an employee that walks out the door with a computer under their arm every day. Both are stealing from you in some fashion.

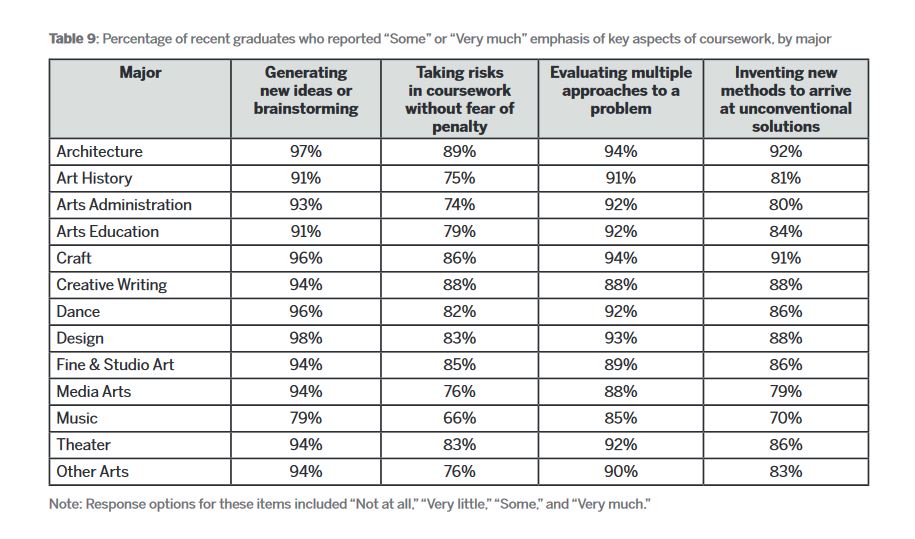

But perhaps most applicable to the argument about the value of liberal & fine arts, culture, creativity, etc is Godin’s assertion that just because they are difficult to teach and measure, doesn’t mean so-called soft skills are not valuable and worth the effort.

We rarely hire for these attributes because we’ve persuaded ourselves that vocational skills are impersonal and easier to measure.

And we fire slowly (and retrain rarely) when these skills are missing, because we’re worried about stepping on toes, being called out for getting personal, or possibly, wasting time on a lost cause.

Which is crazy, because infants aren’t good at any of the soft skills. Of course we learn them. We learn them accidentally, by osmosis, by the collisions we have with teachers, parents, bosses and the world. But just because they’re difficult to measure doesn’t mean we can’t improve them, can’t practice them, can’t change.

Now a slight tangent here– let’s recognize arts and cultural organizations are some of the worst offenders when it comes to hiring for skills and turning a blind eye to poor interpersonal skills because the employee has passion; isn’t getting paid a lot; and there isn’t time or money to train or model proper behavior.

Don’t read Godin’s article and get trapped into thinking about how the arts can help people develop all those soft skills he lists. First, the whole point is to stay away from a utilitarian justification for the value of the arts. Second, as I note, it’s a case of the cobbler’s children having no shoes when it comes to being an exemplar for cultivating those skills in the workplace.

I think the argument to be made is that we can all generally acknowledge that the presence of arts, culture and creativity in our lives enhances society/communities in myriad ways. We can’t measure the benefit specifically or attribute improvements directly and exclusively to the presence of arts & culture. Nor do we want to because creative expression is always going to be one important factor among many (like walkability, public transportation, employment, new initiatives.)

This is important in much the same way as skills like leadership, collaboration, resilience, passion, competitiveness, resourcefulness and hundreds of other factors are important to the success of a business or organization. You can’t set a goal to improve passion by 10% and leadership by 30% next year, but you know you have to work on cultivating both.

You can hire someone based on their sense of humor, honesty and friendliness because you know those factors are important to the effectiveness of your work environment. But no one is hired as the one that fills the humor, honesty and friendliness gap on the team the way they would be for their vocational skills.

Nobody doubts these attributes are important in a business environment even though they can’t be easily measured. In fact, when a young person starts out the are likely to cite these skills in a resume to make up for their lack of experience.

The challenge of the arts and culture community then is to create an environment where the value of the presence, or lack thereof, arts/culture/creativity is acknowledged in much the same way rather than something that can be decanted in discrete amounts.

Yeah I figured they were either box seats or organ pipes. The design suggested there were actual box seats there…