Seth Godin says he figures Apple computers reached their peak about three years ago.

Since then, we’ve seen:

Operating systems that aren’t faster or more reliable at running key apps, merely more like the iPhone…

Geniuses at the Genius Bar who are trained to use a manual and to triage, not to actually make things work better…

Software like Keynote, iMovie and iTunes that doesn’t get consistently better, but instead, serves other corporate goals. We don’t know the names of the people behind these products, because there isn’t a public, connected leader behind each of them, they’re anonymous bits of a corporate whole.

Compare this approach to the one taken by Nisus, the makers of my favorite word processor. An organization with a single-minded focus on making something that works, keeping a promise to users, not investors.

Mostly, a brand’s products begin to peak when no one seems to care. Sure, the organization ostensibly cares, but great tools and products and work require a person to care in an apparently unreasonable way.

If you are nodding your head in agreement upon recognizing that Apple’s achievements have sort of leveled out, stop a second and think about whether you are running things to make them better or just to triage and serve organizational goals.

When I read the sentence about the software not getting better but serving other corporate goals, Trevor O’Donnell’s posts about marketing reinforcing the arts organization’s image of themselves, rather than reinforcing the customer’s image of themselves having a good time, came to mind.

Obviously there is more involved with offering consistently better experiences to those who participate in the events and services you provide than good marketing. Good service, good marketing, good environment are all interdependent.

It is difficult to recognize issues that exist when you are close and involved with them which is why the Apple example is so useful. When we realize that some elements of a highly successful company have leveled off, it becomes a little easier to perceive parallels in our own operations.

The real challenge comes in the last sentence of Godin’s I quoted. What are the areas in which you and your staff can care in unreasonable ways?

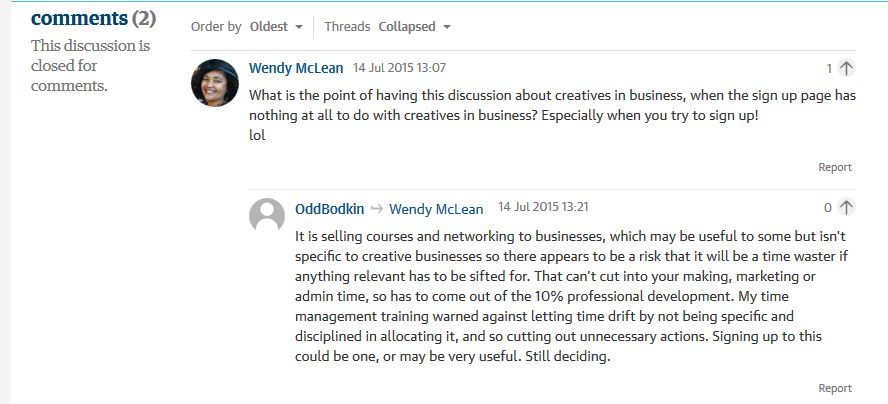

What does that mean? What does it look like for your organization? Your customers can probably give you a hint if you ask (they may be already telling you, emphatically and unsolicited).

There may be people in your organization already invested in something with an unreasonable degree of care who are assets to your organization. It may not be necessary for everyone in your organization to all care about the same thing in order for you to be successful.

Given the number of hats worn by people in non-profit arts organizations, it would be a blessing if you had even a few employees that exhibited unreasonable care in different areas in a manner that was balanced within the organization and within themselves. (Trying to channel unreasonable care into all your areas of responsibility is likely to drive you crazy).

There is another way. The Gewandhaus Leipzig in Germany (concert venue) offers flex- tickets for a small premium. Not an…