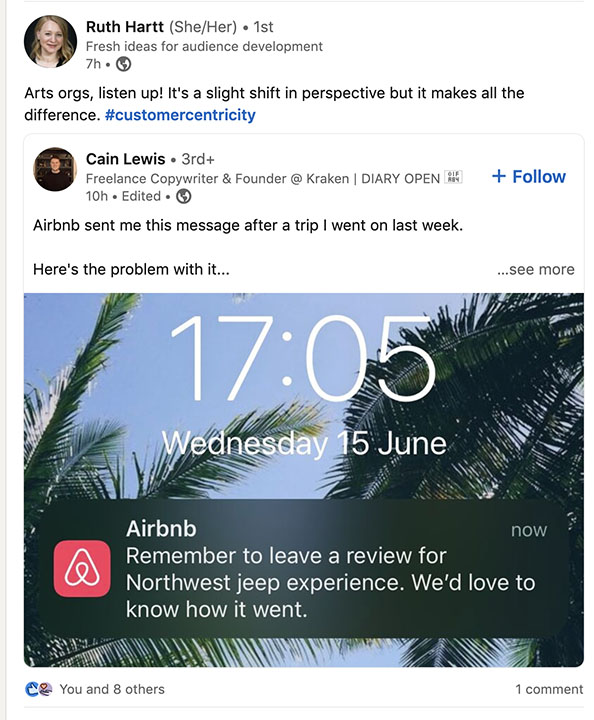

I had planned to write about something different today but this post by Ruth Hartt on LinkedIn grabbed my attention.

Cain Lewis goes on to talk about how he doesn’t care about Airbnb:

So telling me ‘we’d love to know how it went’ doesn’t compel me to leave a review at all 😴

But I *do* care about helping other travellers like me find good experiences. And avoid the bad ones.

Because I appreciate reviews when I’m looking to book something too.

I’d bet most of their customers feel the same way.

So, here’s what I’d change it to:

‘Remember to leave a review for your Northwest Jeep Experience. Your feedback will help other travellers know what to expect!’

Less about Airbnb, more about supporting the community that I rely on so heavily myself.

This got my mind going because Hartt is right, this slight shift in perspective has wider implications. Many arts organizations send surveys after events so directing people to your social media pages when asking people to complete a survey aligns with the concept that their response will help other attendees. Asking people to complete a survey alone based on an appeal to help other visitors know what to expect will likely be met with skepticism.

Even though people may make negative comments on your social media pages, at least those comments are in a place you can see and know about rather than in places far outside your awareness.

Just the same, I think that the perspective of your answers as a participant are making things better for the next person can be applied to surveys that only staff are likely to see. Reframing survey questions in this context can communicate a sincere desire to improve the experience.

For example, instead of asking people how they would rank a performance, the service they received and restroom cleanliness on a Likert scale (1 being worst, 5 being best), questions can ask, “What would you like future attendees to know about our performances/ticket ordering experience/restrooms?

Obviously, it doesn’t have to be that exact syntax repeated for every question, but the general subtext can be present. This line of questioning has “would you recommend us to your friends?” baked into it while adding a sense of “what do you wish you had known/read about us before you arrived?”

For repeat attendees, some of these questions will be a bit less relevant because they are familiar with your physical plant and how to navigate purchasing and attendance. But you can also get feedback about things a first time attendee might think was a one off mistake but a frequent visitor has noticed and wants to warn others about. i.e. “They will tell you they are having problems with X tonight, but it is always like that.”

I also think that asking questions in this manner with a sincere intent to remedy what you can, the first rule of surveying is never ask a question you aren’t willing to act upon, is that it will differentiate your organization from others. Perhaps it will even encourage people to respond to your surveys more frequently.

I know Americans for the Arts are making a strong national survey push over the next year, but their focus is very much on economic impact and asking you how much you spent before you leave the venue. Those who are frequent arts attendees are going to be asked to complete the survey often over the next year. It may be difficult for organizations to find people who are willing to complete their personal, non-AftA surveys, so asking questions focused on the interests of other attendees versus the organizational interest may make the difference.

Just as an added aside – the venue I am currently at will have alternating bursts of reviews for events on our Google profile and Facebook page. I have no idea what the common element is. Why did 10 attendees of a dance recital review us on Google, but a handful of attendees to another event flock to Facebook? Anyone have any insight based on what they have observed?

There is another way. The Gewandhaus Leipzig in Germany (concert venue) offers flex- tickets for a small premium. Not an…