For over a year now I have been excited about the session on writing Requests for Proposals (RFP) Drew McManus and Ceci Dadisman are presenting today at the NonProfit Technology conference so I figure I am pretty much obligated to write a post about it.

(Also I begged Drew to put up a mini-site with the presentation)

I should note, I am not attending the conference. I am just responding to the mini-site Drew has put up with the session content.

Wait! Before you ask yourself why you have read five sentences into a post about something as boring as a request for proposal and haven’t clicked away yet, let me assure you this is valuable info.

The more non-profit organizations depend on websites, social media, email, CRM software, ticketing systems, etc to cultivate relationships with their constituencies, the more it is necessary to make effective choices about the way technology facilitates these interactions.

I have been involved with a number of requests for proposals before and while it is an onerous process, there are some upsides to using it. As well as some downsides, both of which Drew and Ceci cover in the slide deck on the mini-site.

The mini-site covers all the steps, from gathering staff input to define your needs to communicating with different vendors to deciding what process to use. Project Evaluations are an alternative to RPFs, but have their own pros and cons.

The mini-site has a self-diagnosis questionnaire to help you decide which approach might be appropriate to you. (Note the emphatic disclaimer that they aren’t collecting any info on you, including placing you on a cold call list because “that would be a serious d**k move”)

Drew and Ceci solve one of the most frustrating parts of viewing a slide deck outside the context of the live presentation– trying to figure out what the bullet points on a slide really mean– by making their presentation notes available alongside each slide.

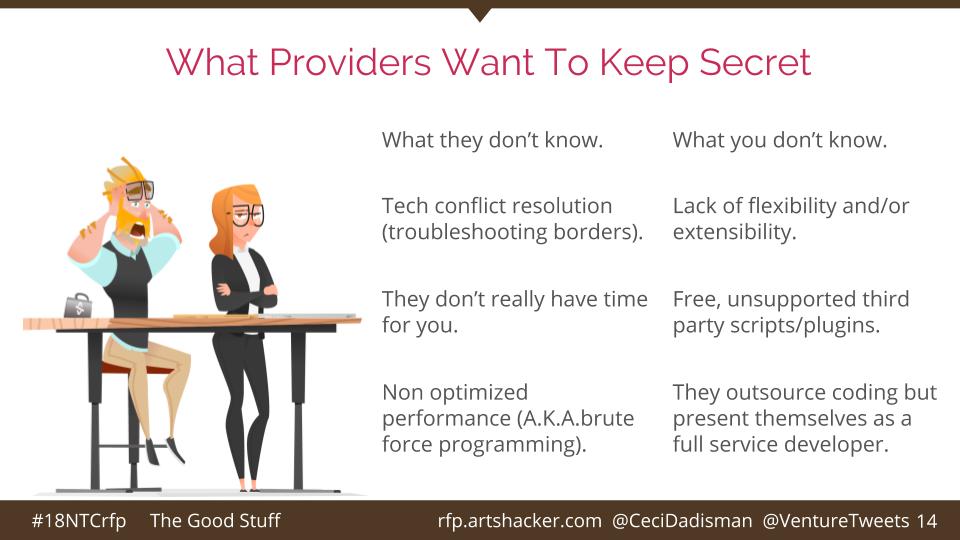

Since part of the title of the presentation promises to tell you about the stuff tech providers don’t want you to know, you will probably want to pay attention to those notes for this slide.

Here is a sample of some of the notes for this slide:

- Tech conflict resolution (troubleshooting borders).

- Some providers are all too happy to let someone else do the dirty work of quality assurance and troubleshooting or blindside you with unexpected fees to carry those tasks out.

- Lack of flexibility and/or extensibility.

- They may deliver on your project requirements but they may not play nice with other providers or make it easy to maintain.

- Free, unsupported third party scripts/plugins.

- Free scripts aren’t bad, but is the provider willing to support them or conflict resolve down the road. Ideally, a provider should provide a line item list of plugins, extensions, scripts, etc. that come from free and paid resources.

- Non optimized performance (A.K.A.brute force programming).

- This is all kinds of important in a post net neutrality world.

- Talk about programming bloat where things work great on launch but performance grinds down over time.

- They outsource coding but present themselves as a full service developer.

- It’s increasingly common for design and branding agencies to project themselves as full web developers when the reality is they outsource coding.

- Examine the difference between coders: frontend UX developer is not the same as a platform programmer.

If any of this starts to concern you, you may want to explore the whole presentation. Not just to raise your awareness about the problems that may arise, but to also become familiar with constructive approaches to the process both for your staff and the people with whom you may end up working.

Thanks for what you are doing to bring cultural change to the arts. It is so important to represent everyone.…