On the Harvard Business Review blog site, Anne Kreamer asks “What If You Don’t Want to Be a Manager?” (h/t Daniel Pink) where she talks a little about the alienation one might feel moving from being a producer of material to a manager. While she talks about an experience in a corporate environment, it was easy to see the same situation cropping up in the arts when someone moves from creating content to producing revenue reports and reviewing labor laws.

One of the options Kreamer suggests, other than leaving the company and striking out on your own, revolves around changing the existing work environment. It was her last two sentences that resonated with me (thus my emphasis).

This is something more companies need to address. To remain globally competitive, organizations need to devise innovative ways to encourage and reward creativity. The unorthodox titles embraced by start-ups — directors of fun, ministers of information — can seem ridiculous, but the emphasis on improvising new ways of doing business is important. Furthermore, research conducted by Office Team found that 76% of employees did not want their boss’s job. If employees are no longer responding to the old carrots, it’s time for companies to establish new means of rewarding talent.

This reminded me of the Daring to Lead and Ready to Lead reports I had written on in the past that reported young arts leaders were chomping at the bit to gain greater responsibility in their arts organization, but didn’t necessarily want to assume an executive role.

It got me to thinking that while there is a lot of discussion about exploring new business models for arts organizations like the B Corporation and L3C, maybe there needs to be a corresponding discussion about changing arts job descriptions so that people actually want to assume the roles.

Two issues that seem to rise to the top for executive directors is work-life balance and that the position seems 75% about fundraising and increasing. It may be time to institutionalize the idea that marketing and development aren’t the sole province of those departments by spreading the responsibility around in job descriptions.

I have read a lot of criticism of Michael Kaiser’s ideas, but I have never seen anyone say he is wrong when he advocates for paying attention to the interests of potential donors and connecting them with your corresponding needs rather than viewing them as the source of a lot of money to answer the need you have prioritized.

With the proper training and expectations declared at the outset, marketing, education and artistic staff could take a more proactive role in identifying, engaging and meeting with donors than they do at present. Hopefully freeing the executive director to balance their personal and professional lives, improve their job satisfaction, connect back with the parts of the organization that excite them, and perhaps encourage others to crave their position.

The same can obviously be done with marketing where development, education and artistic, etc. are more active in expressing and advancing the organizational message.

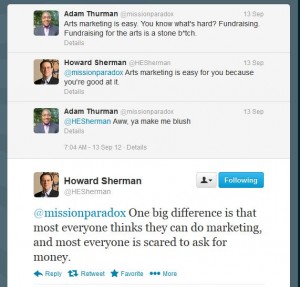

I think people are already cognizant of this interdependent need based on a Twitter exchange between Adam Thurman, Howard Sherman and others this past September.