Like everyone else, I was amazed to read about the recovery of the Ames Stradivarius last week, and the poignant reflections from Roman Totenberg’s daughter Nina, the noted journalist. For me the story had a certain obvious resonance; I remembered the surreal feeling when I received a phone call informing me the Lipinski Strad had been found only nine days after my ordeal began. Imagine waiting 35 years, and finding out the culprit was some nitwit you suspected all along. And that the violin just sat there in a locked case for 4 years after the nitwit’s death until someone decided to take a closer look.

After reading some of the truly sub-literate comments on that NPR page, I thought it might be worthwhile to address certain myths that seem to surface periodically regarding the theft (and recovery) of high-end stringed instruments. Before my own saga, I felt I was fairly well-informed in this area, and considered it due diligence to keep current on the subject. But I’ve also been lucky enough to have the assistance of the FBI’s Art Crime Team, and my knowledge base has broadened considerably. Happily, it turns out that some of the same crowd from my case assisted with the Ames recovery, and I’m sure the Totenbergs are as grateful as I was.

This theft took place in 1980, well before the Art Crime Team or today’s instant mass communication. Even in previous decades, it was still pretty rare to hear about a Strad that disappeared, although if one was stolen deliberately it would often be gone for quite awhile. The internet changed all that, which is a major reason that nowadays these instruments are rarely stolen intentionally. The other reason (obviously related) is that if you do steal one (intentionally or not), there’s literally no market for it. Further, they aren’t “stolen to order”; there’s no Dr. Evil sitting someplace with a fluffy cat in his lap wondering how he can steal the next Stradivarius for his personal use. To my knowledge that’s never happened, and there is no evidence to support that concept.

What typically happens is that these instruments disappear accidentally or almost randomly (or are stolen the same way). Someone leaves it in a taxi, or looks away for a moment in a train station, or steals it off a porch (remember this?). Whoever happens to find it (or take it) either has a huge problem because everyone’s looking for it, or they figure it out and turn it in (or turn themselves in). In this case the perpetrator appears to be deceased, and apparently no charges will be filed. As for earlier efforts by law enforcement, it is sad but true that there was seemingly not enough hard evidence to execute a search warrant on Mr. Johnson over all those years. I suspect he was most likely uncooperative with any investigation, and the options for the authorities are few under those circumstances. In addition, what was undoubtedly a spectacular violin bow by Francois Tourte was not recovered with the Ames violin. It would probably be worth well into six figures by now, and its fate remains unknown.

Until last week I was only aware of three cases in the last 40 years in which a Stradivarius had been deliberately stolen but had not yet been recovered. Thankfully (but tragically), now there are two- the 1714 Le Maurien Stradivari, stolen in New York in 2002, and the Davidoff-Morini Stradivari, stolen in 1995 from the apartment of the eminent violinist Erica Morini. There are similarities between these two thefts, with the instruments taken quietly, then evaporating without much of a trace. According to FBI records, my own case remains the only targeted theft of a specific high-end instrument involving an armed robbery. I hope it stays that way.

Anyone with information about either the Tourte bow or either Stradivari violin above is asked to contact the New York office of the FBI at 212-384-5000 and ask for agent Christopher McKeogh.

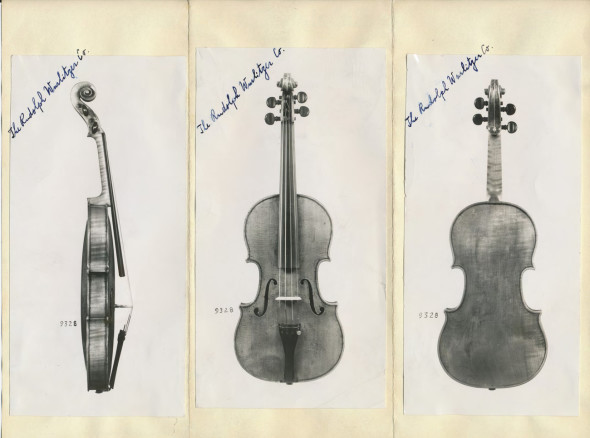

Photo courtesy NPR/Totenberg family

Well said Frank! But as you know, it takes a vigilant violin expert with character to identify and come forward with the truth. I encourage all my colleagues to work on creating a stolen data base that can be shared by all to stop these thefts and recover those that have been lost to time!

Well, there is the Art Loss Register, which is probably the most comprehensive resource at this point, and includes musical instruments. Anyway, the timely dissemination of information on a theft is critical, and most of you in the trade keep tabs on that stuff, whether or not it’s a Strad. And kudos to you for nailing this immediately.

Great article. I think the mystery and allure of how hard it is to pull this off is what drives people to do it. Question: Wasn’t Erika Mortini’s violin stolen in 1995?

Yes, 1995 it was. Thanks for catching that!

I wish I had some information I could give you regarding either of these missing violins, but unfortunately I don’t.

For one year only, before I came to the conclusion I couldn’t hack it, I was a middle-school math teacher in a magnet middle-school in the Washington, D.C. area. As a magnet school, burdened by special bussing from all over the northern part of Prince George’s County, we started later in the day, and ended later as well.

As a new teacher, I was not an efficient time user: I would stay too late, erasing my blackboards with water & sponges, etc., etc. I remember seeing the janitors cleaning the hallways with their huge brooms. They would end up pushing not only pencils, pens, trash & dust down the hallway, but even textbooks, opened to page I-don’t-know-what. I always wanted to unite these textbooks with their student-owners, as if they cared the slightest bit about their missing textbooks, almost as much as I wanted to reunite each lost pencil or pen with its rightful owner!

Imagine how I feel now, wanting to reunite each wonderful musician with their rightful and rare property!

David Pearce,

Washington, D.C.