While people still haven’t returned to the daily routines they may have had before Covid-19 brought a halt to so much of our lives, it might be worth encouraging people to continue cultivating whatever creative practices they may have engaged in during these times. Reinforce the value of whatever they became interested in as part of their lives. Chances are people are reconsidering what things they found fulfilling before and whether those things still hold value for them.

That said, there is always an investment of time and a learning curve involved with starting anything new. That can be a disincentive to continuing for people who are seeking the comfort of their earlier familiar lives.

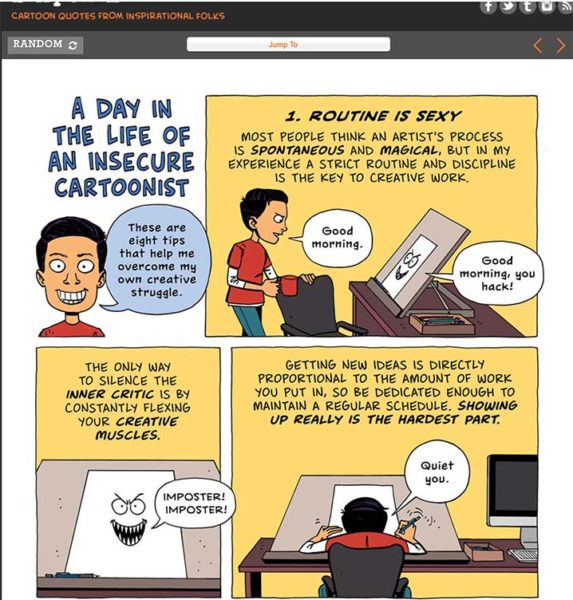

It has been awhile since I linked to a cartoon from the Zen Pencils site. This one is excerpted from a page the cartoonist wrote about his own practice.

Long time readers know before I moved to my current position in Georgia, I lived in Ohio where I tried to infiltrate a Creative Cult, a group of people who provided the community with various hands-on creative experiences at different places around town. They are still up to their shenanigans and currently have people on a hunt around the community trying to find “eggs” that were stolen out of museum paintings.

Nick Sherman, a young gentleman who may or may not be the mysterious, yet dashing cult leader has a weekly newsletter which includes missives to him from the Creative Underground explaining all the ways in which the Man will try to convince him he isn’t creative or that he should be prioritizing other things over his creative pursuits.

For example, on May 1 the Creative Underground wrote:

This is what we mean. THE MAN starts by whispering in your ear something very obvious; that there is a time for art-making, and there is a time not for art-making. A harmless statement right? Wrong! THE MAN never stops where he should. He then goes on to cleverly suggest that, “If you are doing your art, you must be neglecting something else.” Do you see his trap?

Then because you want to be a responsible, upstanding, person you think, “Of course! I do not see my little old grandmother nearly enough.” You go see her. And in this way, THE MAN keeps bringing up distraction after distraction (even legitimate ones!) that keep you from your art. Something always comes up. Soon, your brain makes a very dangerous and direct comparison. It flashes like a bright-red neon sign against the darkest corner of your brain. “ART = SELFISH”

In this way, Nick anthropomorphizes all those insecurities and doubts everyone has about their creative practice. Granted, sometimes there are actually people in our lives who are more than happy to give voice to these sentiments and there is no need to provide them with a metaphoric form.

You can subscribe to Nick’s newsletter here if you have an interest.

Thanks for what you are doing to bring cultural change to the arts. It is so important to represent everyone.…