Thanks to Tim Roberts at Arts Research and Ticketing Service Australia who recently linked to UK Arts Marketing Association’s new Arts Marketing Standards. The standards outline what abilities you should have at four different stages of your career:

Level 1 – Assistant – officer

Level 2 – Senior Officer – new manager

Level 3 – Manager

Level 4 – Head of department/director

These standards are rigorous and thorough. Level 1 standards run 130 pages and each subsequent level adds about 20 pages. Actually, since some of the standards don’t apply to Marketing Assistants, there are many pages that just read “It is not anticipated that Marketing Assistants will have responsibility for…” and it isn’t as intimidating as the 130 page count may seem. On the other hand, the head of department/director has 190 pages entirely full of standards they might be expected to meet.

They also have devised some toolkits to help different entities use the standards:

Employer’s Toolkit

Marketer’s Toolkit

Trainer’s Toolkit

Job Description Templates

The employers toolkit suggests the following use for the standards:

“This booklet outlines how the standards might be used by those working as employers of arts marketers within cultural organisations across the UK to:

•Plan the marketing role/s and job descriptions needed in your organisation.

•Carry out a performance review, building understanding of where the current strengths and skills are within your marketing team and gain a clearer insight into skills gaps within the team

•Input into appraisals and planning of staff training and development

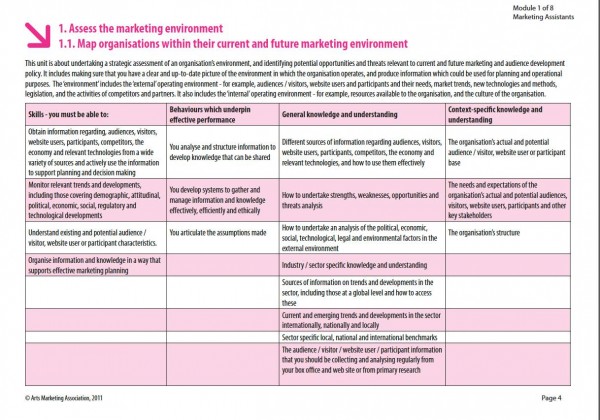

There are eight modules that comprise the full standards. I will leave the reader to explore them all. To give a sample of what is contained, the first module, “Provide marketing intelligence and audience, visitor and participant insight” has 3 subsections the first of which is, “Assess the marketing environment.”

That in turn has three subsections, the first of which is “Map organisations within their current and future marketing environment.”

The standards for that look something like this (click to enlarge):

So the obvious question is, would these sort of standards be helpful for U.S. arts organizations to adopt?

Actually, I don’t think there is any doubt that they would. The true question would be whether they could and would be effectively applied on a large enough scale to bring about meaningful and significant change. If so, should similar standards be developed for other roles within arts organizations?

These standards in conjunction with the toolkits might be of the most help to some of the smallest arts organizations who might have the least experience with marketing. The toolkits provide grids noting the general expectations for different positions normally found in a marketing department including box office. It can help them construct expectations that are suitable to the needs and resources possessed by their organization and make more appropriate hiring decisions. In other words, people may think they need a director of marketing when they need someone to perform the tasks of a manager or senior officer.