I have been pondering whether we should start offering a “Choose Your Own” subscription series in future years. In my past jobs, we never programmed with an eye to filling slots in a series so we offered “Choose Your Own” discounts without any problem. Now I am working in a place which has historically had a number of series and I am looking to offer an additional flexible one.

Since this blog is about discussing practical aspects of arts administration, I thought I would share some of the issues I have been taking into consideration both to solicit some feedback, but also give a sense of the thought process you need to engage in when making these decisions.

The numbers I am using in my example aren’t the actual ticket amounts and they are equal for all events in a series for sake of simplicity. The discount for buying the full season relative to the sub-season pricing is the same though.

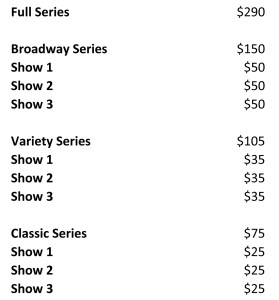

Currently we offer a full season of nine shows ($290) and three sub-seasons of three shows each: Broadway ($150); Variety ($105) and Classical ($75).

My idea for a flex subscription is to offer the sub-season pricing if to any three shows or more shows of your choice.

That might break out as follows:

Instead of buying a series, people would pick and choose from among all the series. Because they are picking and choosing willy nilly, we can’t guarantee them the same seats will be available at every performance, but they still get their seats before single tickets go on sale and at a discount.

Usually the idea behind flex subscriptions is to give people who can’t make it to all the shows in a series the ability to benefit from an advance purchase discount. It is seen as a plus if you can get someone who has historically been a single ticket buyer to commit to attending multiple shows in advance.

But the important issue is the need to factor in the likely behavior of your audience. If there are a lot of single ticket purchases for three or four shows across multiple series in the days right after single tickets go on sale for full price, you need to ask if you think more people will pick up this practice or if you will only end up giving a significant discount to the same group who typically buys tickets at full price months in advance of the show. You could end up losing money in the process.

The same for those who buy the classic series and then one or two tickets to the Broadway series at full price of $65. If there are lot of those, you may end up giving up quite a lot at a $15 difference per ticket.

In our case, our biggest series base is in Broadway with far fewer in Variety and Classic. It wouldn’t represent a significant loss if the Variety and Classic people who buy Broadway tickets at full price received a discount.

My biggest concern is that we may lose full season subscribers to a piecemeal flex series. Every year there is a Broadway show people aren’t crazy about so if Full season subscribers didn’t like one show and picked the other 8 individually, that would represent a $10 loss per subscriber. Not a big deal individually, but if many people made that choice it could be problematic.

The same with the Broadway series subscribers. If they dropped one Broadway show and picked up one Variety or Classic show as their third, that is a loss of $15-$25 per subscriber.

Now the easiest solution to keeping Full Season subscribers from becoming “slightly less than Full Season” subscribers is to place the “Choose Your Own” on the same footing as the other sub-series and limit it to any three events. That way you don’t have to worry about people defecting to a 7 or 8 event subscription.

But if you are in a situation like I was in my last job where you don’t have a large subscriber base, you can go all out and offer discounts on as many shows above the minimum as people care to buy. You have a fair chance of picking up new subscribers.

I will confess I was pretty gung ho about flex subscriptions and the philosophy of giving people the most freedom to choose in return for making that choice in advance. Organizations that kept their audiences tied into a designated series were adhering to a dated concept of audience relations! But as I say, that was when I didn’t have a fairly reliable subscriber base.

Now that I am in a situation where I am doing an analysis of the pros and cons in preparation for pitching the idea to an organization with an established subscriber base, I find myself being a little more pragmatic. (Though note I am still trying to introduce a flexible scheme.)

So what about you? Thoughts about this? Are there packages you have put together to entice people to subscribe that worked? Some that back fired on you and made you lose income or subscribers?